The original Doom, released at the end of 1993, is the first-person shooter. At this point it is a classic staple of the medium and there’s not much I can say about it that others have said better. What I can tell you about is my ambivalence towards it, why that is, and my opinion of its reboot/remake/whatever.

My Highway to Hell

I wasn’t even in my preteens at the time but ultraviolent material wasn’t unfamiliar for me (I loved watching Aliens as a young’un — even got the action figures!) and I did play videogames. Problem is that, overall, I’m not that fond of first-person shooters. Most are amusing but in a fleeting way and few of them — for example, the first installment of the F.E.A.R. series — ever become truly memorable enough to warrant a revisit. It could be argued the devil is in the details, but how many times can you really make shooting a gun from that limited perspective work without getting tiring in some way? At least Portal has puzzle-platforming elements and, though I have yet to play any of it (perhaps in the future!), the Thief series’ emphasis on stealth over combat is far more enticing to me as gameplay.

That is not to say I hated Doom ‘93 — only that I did not share the same enthusiasm as others. I absolutely get why so many like it and would not fault them for it, being a child of the 90’s myself. It was a singular vision by a tight-knit group of friends with highly focused shooting mechanics as well as level design that allowed a wide berth of modification. A cultural product that almost perfectly represented the 90’s attitude of the United States; still reveling in 80’s-style excess and gaudy aesthetics while scoffing at the moralistic hysteria of that decade, often in the form of metal bands ironically embracing Satanism and determined to offend fragile religious sensibilities with lots of demonic imagery and cartoonish viscera, but others tried pushing the envelope whether stand-up comedians or filmmakers in their own way. Along with influence from Dungeons & Dragons as well as Aliens (there it is again!), John Carmack and company at id Software managed to do that with gaming and its legacy remains. Other popular titles at the time either failed to remain relevant, especially Duke Nukem (evidenced by Forever’s abysmal reception from just about everyone), or simply faded from memory save for a niche…

Perhaps I was too young, but there wasn’t any forbidden fruit appeal for me either. Quake, on the other hand, was more enjoyable as a personal experience. That, however, was due to Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor composing darkly atmospheric music for the game more than anything else. I even preferred the original Duke Nukem and I’m honestly embarrassed for having liked that for all the wrong reasons (i.e. sexual titillation). Ultimately, my reasons for liking them had less to do with them as games than having a prominent element that resonated enough with me whether it was musical bliss or perverse indulgence.

All that said: how was the Doom of 2016 (which I shall dub New Doom from here on) as far as the single-player campaign went? It was certainly never as boring as many supposedly realistic, military-themed titles of the same genre have been recently. At least, initially…

Better to Reign Than to Serve

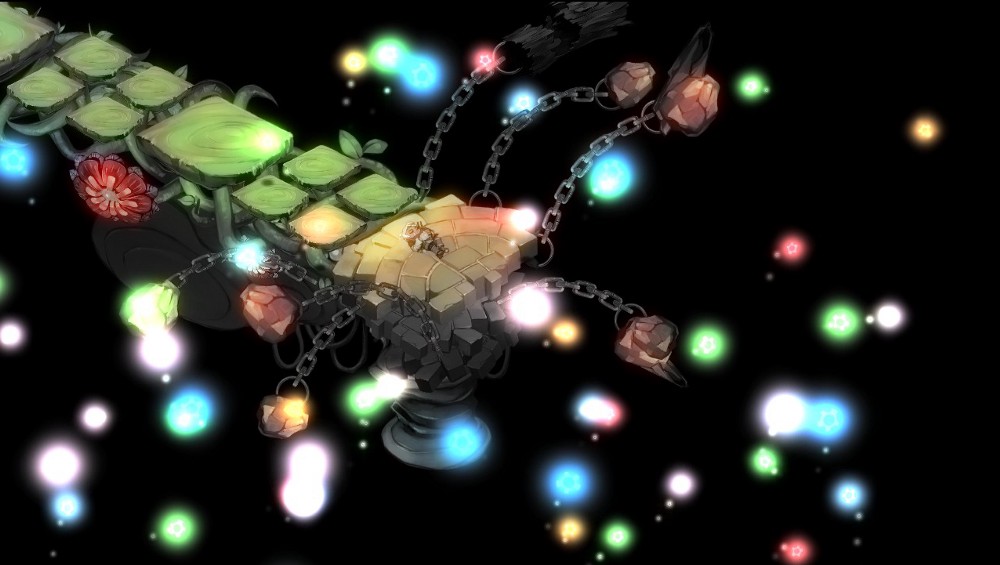

Having fast-paced arena combat over the cover-based kind with old school-style health pick-ups and ammo drops is refreshing, greatly helped by the variety of enemy A.I. and their phenomenal art direction. They aren’t just 3D renditions of their original 2D sprites but revamped with modern tech while still maintaining the feel of being in an interactive death metal concept album of yesteryear. While it would be odd to describe them as “beautiful” — given the malformed and grotesque visages — but are so deeply detailed and textured that it’s hard to think of a better word. The developers could’ve easily fallen into the trap of over-designing them, much in the same way so many latter-day Final Fantasy characters are perplexingly garbed with innumerable belts or Michael Jacksonesque zippers that only makes them harder to tell apart. Every mutated human and unholy abomination is distinct enough that assure these frantic battles never becoming visually confusing. A quick glance is enough to tell you who is who and how to blow them to smithereens.

Even the flimsy plotline has this strange charm, as if it were a somewhat revised schlocky 1950’s B-movie script that managed to attain the high production values of a Hollywood blockbuster. New Doom’s ridiculous story is done in an ostensibly straight-faced manner, but there is a darkly humorous undercurrent when juxtaposed with such over-the-top imagery to the point of being cartoony. It’s hilarious that data files you pick up on Mancubi and the Cyberdemon are dryly-written, stern scientific reports or that the audio logs describing the Doom Slayer’s legendary status among demonkind may as well be from a Todd McFarlane or Rob Liefeld comicbook. It doesn’t break the forth wall constantly, winking and nudging the audience to oblivion, to remind you of how funny it supposedly is even though it only grates. The closest thing to outright self-awareness is how the Doom Slayer’s behavior resembles the mindset of the game’s targeted audience; his only desire to obliterate every monster he crosses, to put an end to this Hellish plague in whatever way possible, and he hates being interrupted from it.

Unfortunately there is the needlessly layered upgrade system so many action games seem to have (perhaps due to some bizarre contractual obligations) but they manage to ease the frustration with some simple solutions. The level design does not waste anyone’s time with each area’s layout magnificently structured — horizontally and vertically — using physical space efficiently for both combat and exploration. You don’t have to search a seemingly endless series of copy-pasted corridors and identical footlockers for items like the haphazardly constructed Shadow Warrior reboot of 2013, thanks to the chainsaw turning enemies into bullet fountains and “glory kills” allowing for regeneration. It helps that one of the special abilities gained indicates all collectibles on the map that — outside of increasing health, armor, and ammo capacity — makes it one of the more useful upgrades available. Not to say those upgrades don’t add variety but, akin to Doom ‘93, each gun (save for the incredibly vestigial pistol) functions normally well enough without any alternate firing modes attached. Such additions come as trying to fix what isn’t broke. Worse, it ends up making the game too easy.

But my favorite feature is the musical soundtrack eerily reflecting the action taking place on-screen. It is clever sound engineering that adds a lot more to the experience than you’d expect but makes perfect sense, as I’ve previously described the game as an interactive death metal concept album of yesteryear. The gunfire and explosions fugue seamlessly with guitar riffs and percussion that make the music more than just being atmospheric — it is the atmosphere. Of all the elements of this reboot, though as modernized as everything else, the soundtrack is the most spiritually faithful to Doom ‘93. They’re a far cry from the midi proxies of Metallica and Slayer songs but it’s not hard to imagine (given Quake) id Software doing similar if they had the resources back then.

Damned to Disappoint…

Now, with all these compliments, one would assume my overall experience was a positive one and changed my sentiment on the series as a whole — but you’d be wrong. As time went on and I reached the end of the single-player campaign, I found myself becoming slowly soured on the whole thing and wondering when it’d finally be over. Reaching the campaign’s conclusion, with its meaningless sequel-hook, did not carry the same sense of elation and fulfillment that came with (say) Metal Gear Solid 3 and its dénouement. Even attempting to replay a level to attain missed collectables was downright painful.

Maybe it’s because, like the majority of first-person shooters, the endless cacophony of bullets being fired and explosions going off become a repetitive chore as the body-count rises with playtime. No matter how refined the mechanics and graphics, or managing to keep the action fast-paced with little dead air inbetween, it needs an element like the aforementioned Portal’s platform-based wormhole puzzles or F.E.A.R.’s intimidating A.I. hostiles. However the Doom Slayer, unlike Chell, is more cumbersome than agile and demonkind far less terrifying than a legion of psychic clones in SWAT gear.

Its God of War-style QTEs are repeated so often that, especially for larger enemies, it feels a bit too effortless and that there’s no serious threat. It lacks tension once one is well-acquainted with the control scheme, supplemented by all the upgrades given, and the whole thing ends up becoming even easier than it already was before. Maybe this is “fun” by those who are who don’t mind endlessly blasting through hell-beasts non-stop but I just find it unengaging without something more. Action without further context or contrast is dull, because spectacle can only go so far before the excitement dissipates and loses all meaning. Without that something — whatever it is — it’s just bells and whistles. It’s a distracting noise that, with enough time, you’ll completely forget after a while.

I suppose it doesn’t help, partly from fatigue and desperation, there’s been a lot of hyperbolic praise attached to the title due to the overexposure and the diminishing returns of series like Call of Duty and Battlefield. It’s understandable to feel such exhaustion given I had it as well — I was already sick to death of all things World War 2, videogames included, before that. The problem, however, comes from people treating the game less like a throwback with a new coat of paint — which is perfectly fine by itself — than it is some kind of innovative entry that redefines the genre when it isn’t that whatsoever. It’s bad enough when the game is at the top of various “best of 2016” lists, which only proves how disappointing 2016 was for videogames, but worse when certain internet personalities make an absurd claim as it being “revolutionary” because of things such as…the variety of QTE animations. Like, really? Have we come to the point where that is considered “revolutionary”? Are our standards so low now that a regression in form is erroneously viewed as progression for such a superficial element? Perhaps I’d be less annoyed if that person, despite rightfully admonishing the company’s odious policy of denying early review copies, didn’t sound as if Bethesda Softworks paid him to give such accolades and promised to be quoted on the the “Game of the Year” edition box art.

To clarify, lest I be misunderstood: New Doom is not a badly-made game whatsoever. On a purely technical level, it is indeed marvelous and one should give credit where it is due. The polish that went into this game’s graphics, controls, and level design are sublime and that’s not surprising with id Software’s history — that is why I started off as complimentary. But, at the same time, functionality and optimal craft alone should not be the criteria as to what makes a gaming experience worth of one’s time and attention overall. If videogames are going to be considered a legitimate form of Art, as I would like them to, then the quality of a game needs to be more than the sum of its most mechanistic parts.

When people defend an otherwise terrible film like, for example, James Cameron’s Avatar by claiming the special effects are impressive — it’s utterly meaningless and beside the point. The elaborate computer-generated imagery does not make up for the complete lack of originality, poor characterization and dialogue, or Cameron’s disingenuously heavy-handed environmentalism (the “noble savage” bullshit wasn’t much better). Perhaps none of that will register upon a first viewing — but it sure will when watching it again or at least thinking about it enough afterwards. That’s not to say New Doom has the same problems as that film (thankfully), just that it’s incredibly overrated and (like my fondness of the original Duke Nukem) for all the wrong reasons.

[Originally posted on 8/7/17 @ Medium.com]