Hey, look, I actually kept my (self-imposed) promise!

This is going to be a pretty brief preamble ’cause – other than my next piece will be the far overdue third part of MCU Catch-Up about Spider-Man: No Way Home, Moon Knight, and Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness – I don’t have much to say other than this’ll be quite breezy compared to the miniature tome (y’know, sorta like the Orange Catholic Bible from Dune – but online!) that was my Elden Ring review.

Oh, and I wrote this prior to us finding out – unsurprisingly – about Justin Roiland’s transgressions. Not gonna defend the guy, ’cause he’s a piece of shit for doing it…

That said: hope you enjoy reading!

Did I ever mention how much I love body horror? I’m pretty sure I have, but just in case I haven’t: I love body horror. I have since I first watched Alien and Aliens when I was…six years old (thank God my parents were that lax). These two games? They’re both full of gross shit!

The New Flesh

Well, actually, High On Life is gross – Scorn is downright disgusting.

The difference between the two can best be described as, respectively, adolescently scatological shenanigans and a morbidly erotic fascination with exploring and manipulating anatomical structures. That’s not to say one is necessarily better than the other as much as they share similarities in subject matter while nonetheless remaining distinct in their execution. Knowing that Rick & Morty co-creator, Justin Roiland, founded the developer of High On Life – Squanch Games – should be enough to tell you what kind of humor is to be expected and it is generally a light-hearted, breezy affair. On the other hand, Serbian developer Ebb Software crafted an oppressive setting that feels like a rotting body being fed on by ravenous necrophages. The player character is little but a weakened red blood cell that hasn’t died or succumbed to a cancerous infection – or, at least, not yet.

One’s mileage will inevitably vary when it comes to High On Life’s form of comedy, but speaking only for myself, it’s more miss than hit since it goes for quantity over quality. There’s more consistency and better comedic timing within a 22-minute episode of Rick & Morty or Solar Opposites, but High On Life’s jokes often overstay their welcome by either oh-so-ironically overexplaining themselves or by dropping too many allusions to other pop culture properties at once. The latter can, on occasion, end up working from time to time. A favorite of mine is a phone booth in the game’s hub city, leading to a series of awkwardly one-sided diatribes to the taciturn player character, which’re eerily reminiscent of the collectible conversations featured in The Darkness. However, it’s far less amusing when a character brings up various anime (or anime-inspired cartoons, in Code Lyoko’s case) as well as Final Fantasy VII while using a diagonal elevator when going from one part of a level to another.

Shut. The. Fuck. UP!!!

Scorn is an acquired taste, a very specific acquired taste; like sardines if their pungent scent and bitter taste came with an equitable sense of existential horror and the kind of shock-induced nausea from witnessing a freshly-made murder scene. It is not fun or exciting, there is no empowerment or satisfying closure, and hope for relief in a pleasant end is what fuels the unpleasantly biomechanical nightmare. But, of course, hope can only go so far. It’s closer to an interactive H.R. Giger painting than either Darkseed or its hilariously terrible and interminable sequel. Well, technically, an H.R. Giger and Zdzisław Beksiński painting – according to the developers – but it’s definitely more Gigeresque than Beksińskian. As much as I’ve described this game in the least appealing way imaginable, I happen to be an admirer of both Giger and Beksiński’s work, and that ended up making the experience far more engaging for me than it was for either Ben Croshaw or Jim Stephanie Sterling. I can’t fault either of them because, again, it’s a very acquired taste.

Now, what do you do in these games? You shoot things with a gun, of course! Well, kinda.

That’s Not A Gun…

The guns in these games are alive. Quite literally.

High On Life’s Gatliens (admittedly, I do love that portmanteau) can speak and are voiced by a handful of comedians – Roiland himself, Betsy Sodaro, J.B. Smoove, and Tim Robinson – to varying degrees of success. I know Roiland has more range, as a voice actor, but he’s relying too heavily on sounding like variations of Rick & Morty’s titular characters and ends up delivering the majority of that aforementioned deluge of oh-so-meta and irony-poisoned jokes. Sodaro and Smoove are fine, I guess, but they’re also given the least amount of dialogue and not given much characterization despite the room to do such. Like, they have lines of dialogue but they’re more like placeholders in a script instead of attempting to further develop them as individual companions.

It’s unfortunate Tim Robinson ends up being the odd one out. His Gatlien, Creature, is the final of the four to be attained yet gives the best performance in the game. Perhaps I’m biased, as I Think You Should Leave is comedic gold to me (“Tables are my corn!”), but Robinson excels at playing ostensibly congenial individuals who gradually reveal themselves to be mentally unhinged. Unlike the series, the game ends up making Creature more endearing than disconcerting, which easily makes them the best character in the game. You can’t help but find it tragic, yet heartening, that a person who’s been experimented upon and became brain-damaged from the process, and who’s accompanied by a sense of self-hatred, never loses their sense of empathy and compassion for others. Plus, like, there’s an entire section where he uses a Transatlantic gumshoe affectation that’s wonderful music to my detective-noir-loving ears.

How the Gatliens function in the main gameplay loop, save for Creature (of course), is equally disappointing. Kenny (Roiland) functions as a typically underpowered semi-automatic pistol, Sweezy (Sodaro) is a submachine gun that wouldn’t be out of place in the Halo games, and Gus (Smoove) is a piss-poor shotgun with a vestigial special function. Creature, on the other hand, is an amusing take on a grenade launcher, but each round is their suicide-bomber offspring who latch onto enemies to cause damage like a combination of Mr. Meeseeks and the claymation homunculi from TOOL’s “Schism” music video (which does, in fact, live rent-free in my head). Only when the game moves away from gunfights and into exploration are the Gatlians and your lone melee weapon (a living knife named…”Knifey”, voiced by Michael Cusak) at their most interesting.

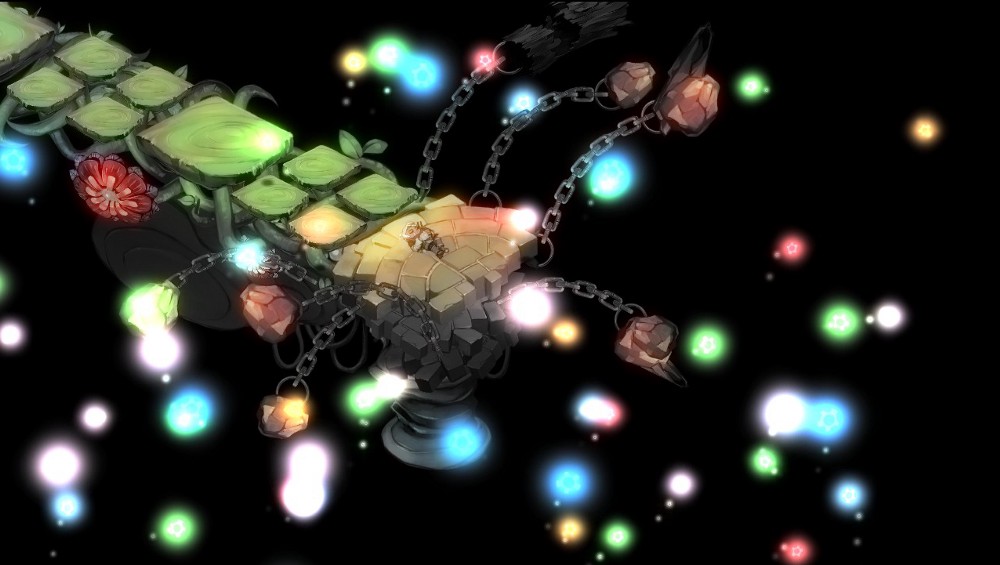

Bloodsucking Stringbean Homunculi

Platforming mechanics with 3D graphics have always been fraught with issues – some of which High On Life displays – but I’m also reminded of how thrilling it is when done right. I mean, it’ll never feel as satisfying as web-slinging around Manhattan in the recent Spider-Man games, but High On Life’s attempts are an improvement on the mechanics in Quake and on par with the earlier Rachet & Clank titles. There’s a level of nostalgia to it, making me feel warm and fuzzy on the inside, but it still manages to make you recollect each and every wart. It’s imprecise and the environment doesn’t always indicate what is or isn’t reachable (‘cause invisible walls), leaving certain sections an exercise in aggravation, but it’s more memorable than the flaccid gunplay that feels only a few steps above Chex Quest. Unless, like, that was the point in the first place…?

Where Scorn differs, besides the extreme opposite in tone, is that there’s really only one gun. Though that’d be inaccurate as it’s actually a living gun handle with detachable, interchangeable heads to operate (respectively) as a giant melee cattle gun jackhammer, pistol, and shotgun. There is a grenade launcher, but it comes late in the game and is barely used for combat. In true survival horror fashion, the gunplay is tertiary to the exploration and environmental puzzle-solving, akin to pushing buttons and pulling levers in the right order for the world’s most stomach-churning Rube Goldberg machine. The buttons and levers (obviously) are shaped like wet, glistening orifices and appendages with cogs that sound like creaking bones or the tearing sinews of muscle when they move.

The reason I haven’t mentioned ammunition as a factor in gameplay is that, in High On Life’s case, it doesn’t really matter. Each Gatlien has limited rounds that can be fired before needing to be reloaded – but the pool of rounds itself is technically unlimited. The logic behind it (if you can call it “logical”) is that, in being living creatures as opposed to constructed tools of warfare, the ammunition they use is actually bodily excretions that’ve been weaponized. Again, it’s a gross game like that, but…that doesn’t make sense either. You only need to feed the Gatliens spikey fruit in order to use their special abilities in combat which, while it serves a mechanical purpose, makes you wonder how they can still endlessly produce piss/shit/kamikaze babies without having appetites that’d put all the Hobbits of Middle-Earth to shame. Maybe I wouldn’t care so much if the game itself didn’t spend so much time calling out the ridiculousness of its own premise.

Scorn, however, is far more interesting in the presentation and usage of ammunition within gameplay. Its lack of explanation for, well, anything ends up working in its favor. As Scorn’s world is one where the biological and mechanical have been melded together into something entirely new and are now inseparable from one another, the living weaponry simply sustains itself by performing its designated function. What it uses as projectiles is neither spit, mucous nor bile – it’s dentata. It is teeth. Motherfuckin’ bullet teeth.

Oh, do you think my references to the filmography of David Cronenberg began and ended with the first section’s title? Well, yeah, you were totally wrong – especially when there’s an even more apropos entry than Videodrome!

Just say it with me, y’all: eXistenZ…

Y’see, High On Life is too high on its own supply of farts and “I don’t care” pretension rather than being genuinely earnest enough to ever present any meaningful commentary about the medium. I mean, how could it, when there’ve already been dozens of other videogames being all self-aware about the absurdities of their medium for years now? Even though eXistenZ did it before all of them – much like how Mystery Men did for superhero movies, far before they gained worldwide popularity. It took the interactivity of videogames as a medium to its logical (and grotesque) extreme. It showed what a fully dissociative experience would result in when the walls between reality and fiction are blurred, beyond both physical and psychological comfort.

Scorn evokes similar themes itself without a single line of dialogue or smug color commentary in order to do so – it does far more with less, while High On Life does very little with too much.

Xenomorphosis

Maybe, had it been developed and released during the early 2000s, I’d have loved High On Life – or, at least, a game like it since Rick & Morty wouldn’t exist for several years. I’d even give it some slack were it simply an earnest throwback to that particular decade of first-person shooters, instead of jumping on a bandwagon that was already running on fumes. But, no, it had to decide to follow a trend…

Honestly, fuck meta-commentary, comedic or otherwise. Its pervasiveness in entertainment has turned it into a crutch for a haphazardly-constructed plot and half-baked characterization rather than any actual deconstruction of narrative tropes. As if the story is endlessly winking and nudging you to affirm that, yes, everything happening is very silly don’t-cha know it! But those observations, simply by themselves, just aren’t funny. There needs to be more to it, and that happens when you have well-defined characters who bounce off one another in absurd-yet-interesting situations.

I’m probably not going to play High On Life again, and I sincerely doubt anyone will remember it a year or so from now. I also doubt this game could’ve existed without Rick & Morty’s popularity and acting as [Adult Swim]’s flagship title. As if it was made not because it was an original idea people felt enthusiastic enough about to make manifest but as merchandise for the Roilandverse. I can only hope, in Scorn’s case, that its current lack of exposure and attention eventually leads to a delayed appreciation – ‘cause, and I’m entirely serious saying this, it’s a masterpiece. The game’s development feels like a product of love and dedication, moreso given just how idiosyncratic it is as a title in the current industry, and – when looking into it further – they left a lot on the cutting room floor to make the final version possible. It’s a game I do, in fact, want to replay in the near future.

“…k i l l….m e…”

Scorn is something that, though far from easily palatable, is a brief yet incredibly unique experience you don’t see much of elsewhere. It’s an immersive mood piece that cares little for player empowerment or even a sense of closure, and there’s still a lot of value in that – not every film, series, comicbook, or novel “needs” to be fun either. It’s worth some consideration, even at a significant discount, than to have never tried it at all…

Um, yeah, got nothin’ here.

See y’all next week!